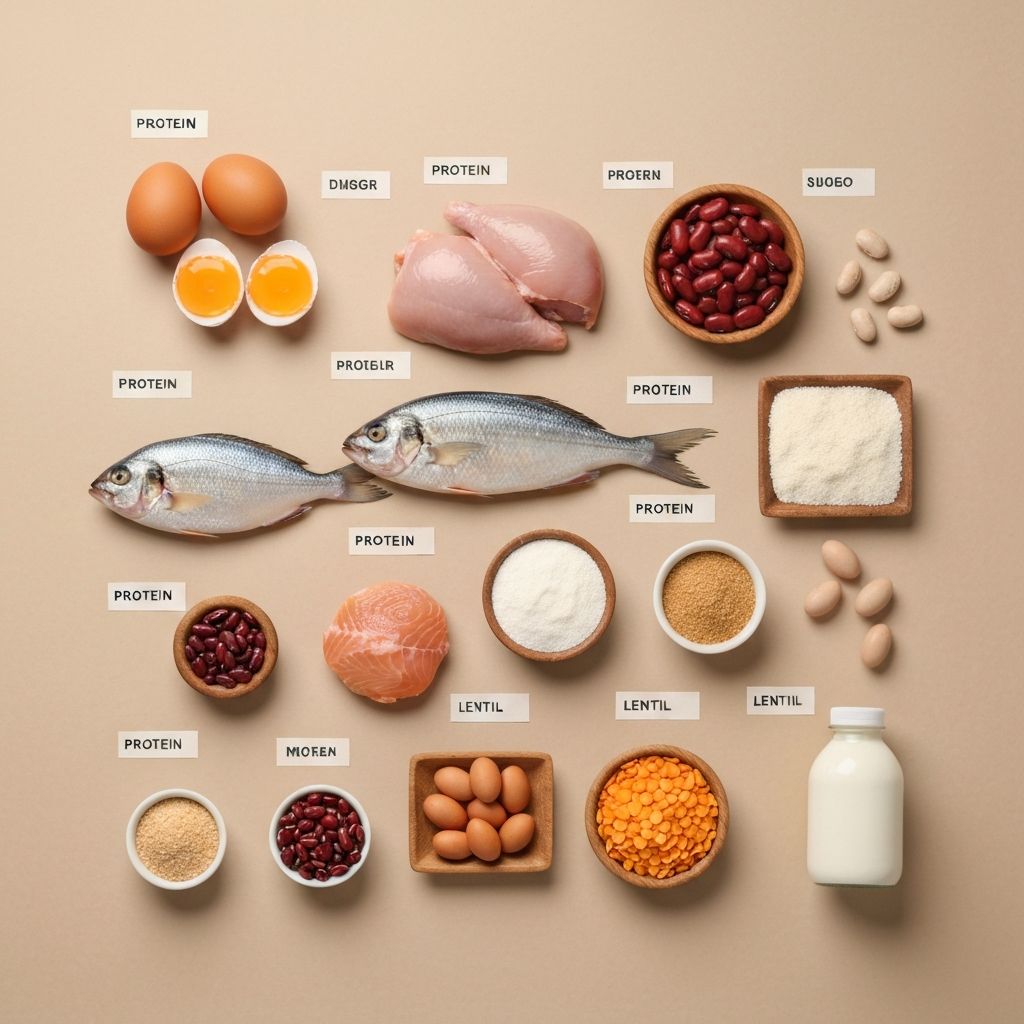

Protein Bioavailability Across Food Groups

Protein bioavailability represents the degree to which consumed protein amino acids become absorbed and available for physiological utilization. This metric encompasses digestibility, absorption efficiency, and the biological value of protein after utilization in human tissues. Bioavailability varies substantially across food categories based on protein structure, antinutrient content, and food matrix composition.

Digestibility and DIAAS Comparison

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) provides standardized bioavailability assessment across food sources. DIAAS values range from 0 to 1.0, with higher values indicating greater digestibility and amino acid availability. Animal-derived proteins consistently demonstrate DIAAS scores approaching or reaching 1.0, reflecting their structural composition minimally complicated by antinutrient factors. Plant-based proteins demonstrate substantially lower DIAAS scores, typically ranging from 0.4 to 0.8, reflecting residual antinutrient effects even after cooking.

| Food Category | Example Sources | Typical DIAAS Range | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Proteins | Eggs, poultry, fish, beef, dairy | 0.95-1.0 | None |

| Legumes (cooked) | Lentils, chickpeas, beans | 0.4-0.8 | Phytic acid, tannins |

| Whole Grains | Wheat, rice, oats, corn | 0.4-0.7 | Phytic acid, reduced lysine |

| Nuts and Seeds | Almonds, peanuts, hemp | 0.5-0.7 | Phytic acid, fat interference |

| Soy Products | Tofu, tempeh, edamame | 0.9-0.99 | Minor compared to other plants |

Antinutrient Effects on Bioavailability

Plant-based proteins commonly contain compounds that reduce digestibility and mineral absorption. Phytic acid binds minerals and forms complexes that impede protein digestion. Tannins similarly reduce digestibility through protein precipitation and enzyme inhibition. Protease inhibitors directly inhibit enzymes required for protein breakdown. These compounds accumulate in seed structures, serving botanical functions of defense and germination regulation. Cooking substantially reduces antinutrient concentration through thermal denaturation and compound degradation. Extended cooking at high temperatures further enhances bioavailability through protein denaturation improving enzyme access.

Food Matrix Effects on Absorption

The food matrix—the structural arrangement and accompanying components of protein—substantially influences bioavailability independent of intrinsic protein quality. Dietary fat slows gastric emptying, extending protein exposure to digestive enzymes and potentially enhancing amino acid absorption. However, extremely high fat content can impair digestion through prolonged gastric transit. Dietary fiber can reduce protein digestibility through physical encapsulation and interaction with digestive processes, though moderate fiber intake does not substantially compromise protein absorption in whole food contexts. Carbohydrate composition influences postabsorptive metabolism through insulin signaling, affecting amino acid fate in tissues but not absorption efficiency itself.

Amino Acid Absorption Kinetics

Individual amino acids undergo absorption through distinct transport mechanisms, creating variable absorption timing. Some amino acids rapidly enter circulation within 30-60 minutes, while others absorb more slowly. This variability in amino acid biokinetics influences postprandial (after-meal) amino acid patterns and metabolic response to consumed proteins. Animal proteins with high leucine and branched-chain amino acid concentration generate more pronounced insulin secretion and anabolic signaling compared to plant proteins with more modest branched-chain amino acid concentrations. These distinctions separate the biochemical characteristics of protein sources without implying superiority of animal over plant sources, but rather describing physiological differences.

Cooking and Processing Effects

Cooking generally improves protein digestibility through several mechanisms. Heat denatures native protein structures, improving enzyme access and facilitating amino acid release. Extended cooking at high temperatures can generate advanced glycation end products through browning reactions, which may reduce digestibility of specific amino acids. However, moderate cooking substantially enhances bioavailability compared to raw foods. Fermentation processes—employed in production of tempeh, miso, and traditional foods—enhance bioavailability through microbial enzymatic degradation of antinutrients. Sprouting similarly initiates enzymatic processes that improve nutrient bioavailability. Processing through grinding or pureeing increases surface area for enzyme exposure, potentially enhancing digestibility independent of cooking.

Individual Variation in Bioavailability

Bioavailability assessment using DIAAS and other metrics derives from standardized laboratory measurements that may not perfectly reflect individual human variation. Digestive enzyme activity, gastric acid secretion, intestinal transit time, and gut microbiota composition vary among individuals based on age, health status, and previous dietary exposure. These variables can influence practical protein bioavailability despite standardized DIAAS assessments. Elderly populations and those with compromised digestive function may benefit from more digestible protein sources, while healthy adults typically efficiently absorb protein across diverse food sources when consumed in adequate quantities and appropriate food matrices.

Educational Context

This article presents research-based bioavailability data for informational purposes. Individual protein absorption and requirements vary based on age, digestive health, and personal circumstances. Dietary decisions reflecting personal circumstances and individual tolerance remain appropriate across diverse bioavailability profiles.